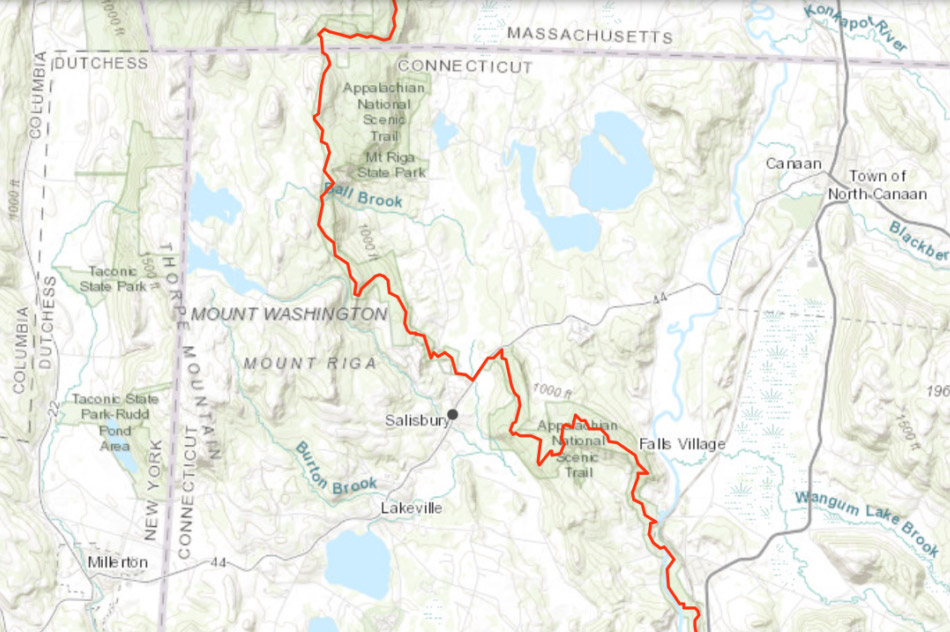

The 60.1 square miles that comprise the town of Salisbury contain terrain that is as varied as it is beautiful. In it, you can read the history of millennia of geological time, as well as the more recent history of European settlement. Salisbury is the northwestern-most town in the State of Connecticut. It is bound on the east by the Housatonic River, and on the north it shares a border with Massachusetts through the Taconic Range and the valley east of the mountains. On the west Salisbury stops at the Connecticut/New York state border, which runs through the Taconics and just west of Indian Mountain. The town of Sharon is on Salisbury’s southern border. There are six large lakes within the Town’s boundaries.

Colliding proto-continents, massive pressure and heat, crumpled, folded and uplifted crust, volcano chains, continents ripping apart, rifts, erosion that turned 20,000 foot peaks to hills, long-gone oceans. Mixed repeatedly over a billion years, these are the ingredients that formed the landscape we see around us. The process also formed the “basement” bedrock that underlies the northwest corner.

Generally unseen well below the ground we walk on, in some regions this metamorphosed rock was thrust to the surface in the geological mixing process. Visible in outcroppings of Hudson Highlands, Berkshires, and Taconic Range are the remnants of the ancient Grenville and Taconic mountain chains. Formed of tough and weather resistant schist, gneiss, or granite these rocks have resisted eons of erosion. More specifically, schist predominates as the bedrock in the higher elevations of Salisbury.

Geological mixing also created another form of bedrock underlying Salisbury: marble. This is the basement rock in the area from the Twin Lakes stretching southwest to the Sharon border and is also found in the Housatonic River valley. Known as Stockbridge Marble, it is the remains of a shallow sea; the carbonate mud (comprised of skeletons of microscopic sea creatures) metamorphosed into limestone and eventually into marble. Because of its limestone heritage, marble is not as resistant to weathering as schist or gneiss. It has been subject to the erosive effects of our naturally slightly acidic rainfall and the rush of streams over millions of years. The result are the lowlands carved out by the Housatonic and the depressions that allowed the formation of Salisbury’s lakes. Marble deposits were quarried beginning in the 1700’s for the lime used to remove impurities in the iron making process.

Salisbury did not escape the Ice Age. Glaciation began almost 2 million years ago. During the most recent ice advance (the Wisconsin Ice Age, beginning about 75,000 years ago), it is estimated that the ice in the area was one mile thick. The continual polishing of the ice as it advanced and the tremendous flow of meltwater as it retreated transformed previously V-shaped river valleys into U-shaped valleys, smoothed and rounded hills, and scoured out lake basins such as that of Lake Wonoscopomuc.

In addition, as the ice retreated about 12,000 years ago, it left glacial till and melt water deposits on the surface of the bedrock, hundreds of feet deep in some spots. Glacial till is comprised of gravel, sand, silt, clay, rocks, and boulders and is termed “unsorted” since it is impermeable and inhibits water drainage. Meltwater deposits, while they also include gravel, sand, silt, and clay, are “sorted” and form well-draining, fertile soil. The sand, gravel, and clay left by the glaciers on the surface of the land can be easily mined and is used in construction and to manufacture concrete, bricks, and pottery.

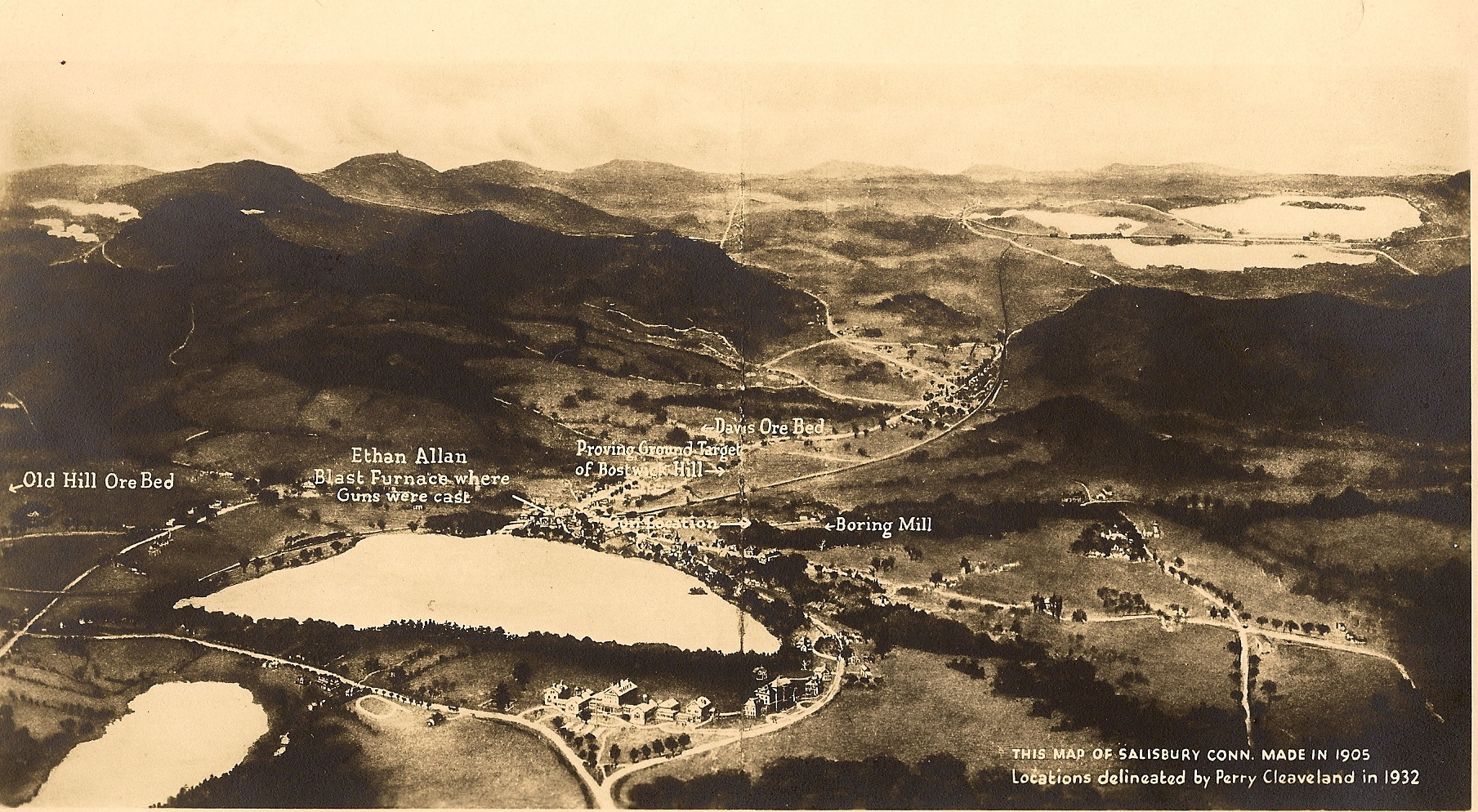

The geological history of the Northwest Corner set the stage for the early history of the town of Salisbury. The iron ore, marble (which was mined for the lime it could yield), streams, and forests created over millennia were all essential to produce the iron that was the foundation of Salisbury’s growth and prosperity in the 1700’s to the early 20th century.

Taconic Mountains

The name Taconic is translated from Algonquian as meaning “in the trees. The geologic origin of these mountains is described above. Part of the Appalachian mountain chain, their length is variously reported as 150 or 200 miles. Wikipedia reports that since the southern end of the range “fade[s]” into the geologically related eastern arm of the Hudson Highlands, it is difficult to ascertain the southern beginning of the range. On its northern terminus the mountains “dwindle into scattered hills and isolated peaks” near Rutland, VT. Wikipedia further reports that it is incorrect to group the Taconic Mountains with the BerkshireMountains or the Green Mountains, which are east of and geologically distinct from the Taconics. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taconic_Mountains

While the exact extent of the Taconics is open to debate, it is certain that the highest point in Connecticut can be found in Salisbury, at the 2,379 foot mark on the southern slope of Mt.Frissell (whose peak is actually in Massachusetts). The honor of highest peak in the state can also be found within Salisbury’s borders: Bear Mountain at 2,326 feet.

Iron

The most abundant element within Earth as a whole, iron is the fourth most common element in the earth’s crust. A sedimentary rock, iron ore is believed to have been formed at least two billion years ago as iron in the earth’s oceans combined with the oxygen then being released by the first creatures capable of photosynthesis. Over time the geological forces noted above also folded and lifted the ocean floor and its iron-rich rock into the mountains around Salisbury. In 1731 iron ore was discovered at Ore Hill in Lakeville, and the Iron Rush was on. Iron was produced in Salisbury until the early 20th century.

Housatonic River

The river rises from four sources in the Berkshires near Pittsfield, MA and travels 149 miles to empty into the Long Island Sound between Stratford and Milford. It drains a watershed of 1,948 miles. The name Housatonic is derived from Algonquian, meaning “beyond-the-mountain-place.” Approximately 15 miles of the Housatonic flows through Salisbury. Over the centuries the river has been a source of power for paper, iron, textiles, and electricity industries. Ames Iron Works, established in 1833 in the Amesville section of Salisbury, made use of river power in its production of iron wheels and axles, cannons, and cannonballs. Today FirstLight Power operates a hydroelectric plant on the Housatonic across from the Amesville section of Salisbury. Salisbury’s section of the river is popular for swimming, canoeing, kayaking, and fishing.

Lakes

Salisbury is fortunate to be home to six lakes, comprising almost three square miles of the town’s total area.

Riga Lake and South Pond (originally Forge Pond)

are lakes privately owned by the Mount Riga Corporation. Mount Riga was the site of an iron furnace built in 1762 and was a prosperous town of 1,200 until the iron ore petered out. The furnace closed down in 1847, and the town dwindled. Descendants of the original iron workers own the land through the Mount Riga Corporation. The lakes have water shed of 3,600 acres and flow into Wachocastinook Creek, a tributary to the Salmon Kill.

Washining and Washinee Lakes (the Twin Lakes)

are in the northeast corner of Salisbury. The two lakes are connected by a narrow channel. Washinee Lake is the western most lake and is smaller (at 260 acres), shallower, and less developed of the two. After the Civil War, it was bisected by a causeway carrying the track of what was initially the Connecticut Western Railway and, after several changes in ownership, the Central New England. The causeway no longer spans the lake. Washinging Lake covers 562 acres and is surrounded by second and full-time homes. It offers boating and fishing (large mouth bass, chain pickerel, black crappie, yellow perch, brown bullhead, sunfish, Kokanee salmon, and trout). Isola Bella, the only island in the lake, is connected by a causeway to the shore. Bequeathed to The American School for the Deaf in 1963, it operates a summer camp on the island.

Lake Wononscopomuc

is located in Lakeville and sometimes called Lakeville Lake. At 102 feet it is the deepest lake in Connecticut and is 348 acres in area. The lake is fed by underground springs and was formed during the last Ice Age. Today the Town Grove is a beloved Salisbury park, offering swimming, boating, picnicking, and fishing. The lake is known for trout, large mouth bass, pickerel, yellow perch, and sunfish.

Wononpakook Lake

is also known as Long Pond and is the southern most lake of the six, is a shallow, mostly undeveloped body of water. The Hotchkiss School’s Beeslick Woods comprises most of the eastern shore of the lake, while the Sloan YMCA camp and Mary Peters Park abut the western shore.

Forests

It is hard to believe living in Salisbury today that, beginning in the 1700’s and into the 19th century, the hills and valleys of the town were stripped of trees to supply charcoal to the 43 iron furnaces in operation, provide fuel for heating and cooking, and clear the land for farming. Today the land is covered with mature secondary growth. The predominant species of trees in the Northwest Corner are oak, hickory, beech, maple, birch, and white pine.

Public Land

There are several small town-owned parks in Salisbury: Mary Peters Park, Edith Scoville Memorial Sanctuary, the Town Grove. Mount Riga State Park is the only state park within the town’s boundaries. It is accessible from the Undermountain trailhead on Route 41, which climbs about 1,700 feet to Bear Mountain. Through its Land Trust, the Salisbury Association has protected 3,500 acres in Salisbury through conservation easements or outright ownership. Some of these properties are open to the public for hiking. Please see the Land Trust page on this website for more information. (click here)

Appalachian Trail

The most well-known hiking trail in Town, approximately 20 miles of the 2,190 mile long AT run through Salisbury. It climbs down from Sharon Mountain near Route 7 and just south of route 112, passes Housatonic Valley Regional High School, climbs Wetauwanchu Mountain west of Falls Village, crosses Route 44, and heads up to the Taconic Plateau from the trailhead north of Town on Route 41. The trail is popular not only with through-hikers but also with those of us who cherish the beautiful landscape of our Northwest Corner neighborhood.

Reference List

REFERENCE LIST

Alter, Lisa. Geology of Connecticut, Curriculum Unit 95.05.01. Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute. https://teachersinstitute.yale.edu/curriculum/units/1995/5/95.05.01/2.

REFERENCE LIST

1. Alter, Lisa. Geology of Connecticut, Curriculum Unit 95.05.01. Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute. https://teachersinstitute.yale.edu/curriculum/units/1995/5/95.05.01/2.

2. Bedrock Geology Map. Connecticut Environmental Conditions Online, a collaboration of the Connecticut DEEP and the University Center for Land Use Education and Research. http://cteco.uconn.edu/maps/state/Bedrock_Geologic_Map_of_Connecticut.pdfhttps://portal.ct.gov/DEEP/Geology/Statewide-Geologic-MapsBell, Michael.

3. The Face of Connecticut. Hartford, CT: State Geological and Natural HistorySurvey of Connecticut. 1985. Accessed 1/25/21. http://70.91.221.154/face_of_ct/Gaige

4. Michael & Glogower, Yonatan. A Fieldbook: Great Mountain Forest. Yale GlobalInstitute of Sustainable Forestry.

5. New Haven: Yale University. 2016.http://www.greatmountainforest.org/education/research.php“Geology of the Housatonic Valley.”

6. Housatonic Valley Association.https://hvatoday.org/geology-housatonic-valley/“History.”

7. Twin Lakes Association.http://twinlakesassociation.org/about-us/“How Iron is Made.” How Products are Made. http://www.madehow.com/Volume-2/Iron.htmlKing,

8. Hobart M. “What Is Iron Ore, How Does It Form, and What Is It Used For?”Geology.com. https://geology.com/rocks/iron-ore.shtmlKirby, Ed.

9. Exploring the Berkshire Hills—a Guide to Geology and Early Industry in the UpperHousatonic Watershed. Greenfield, MA: Valley GEOlogy PUBlications. 1995.

10, Kirby, Ed. Echoes of Iron. Sharon, CT: Sharon Historical Society. 1998.

11. Kirby, Ed. (August 31, 2012). “Salisbury Iron Forged Early Industry” Connecticuthistory.orghttps://connecticuthistory.org/salisbury-iron-forged-early-industry/Kirby,

12. Ed. “Geographic, Topographic and Geological Review”. The Sharon Land Trust.https://sharonlandtrust.org/about-sharon/geography-of-sharon/McChord, Jr.,

13. Winfield. History of the Twin Lakes and Isola Bella. American School for the Deaf. https://www.asd-1817.org/programs/camp-isola-bella/historyMiller,

13. Robert (June 30, 2018). “Ancient marble vein runs through Western Connecticut.”https://www.newstimes.com/news/article/Robert-Miller-Ancient-marble-vein-runs-through-13038490.php“Mount Riga Ironworks.”

14. Wikipedia.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mount_Riga_IronworksNatural Resources Inventory.

15. Salisbury, CT: Town of Salisbury. 2009.“Salisbury, Connecticut.” Wikipedia.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salisbury,_ConnecticutSills, Norm.

16. Salisbury—from Primitive Frontier to Flourishing Town. Salisbury, CT: SalisburyAssociation.

17. 2005. Smith, Seymour. 1976. Doll, Chuck updated 2006. “Northwest Camp—Mt. Riga.

18. ”Connecticut Appalachian Mountain Club.https://ct-amc.org/nwcamp/mtriga/Spelbos, Jos & Murphy, Wendy.

19. Chapter on Geology in Natural and Cultural Riches of Kent,CT. Town of Kent, CT Conservation Commission. 2002. https://www.townofkentct.org/conservation-commission/pages/natural-cultural-riches-kent-ctStoffer,

20. Phil & Messina Paula. Geology and Geography of New York Bight. The HighlandsRegion chapter. CUNY Earth & Environmental Science Ph.D Program. 1996.http://www.geo.hunter.cuny.edu/bight/highland.html“Taconic Mountains.” Wikipedia.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taconic_MountainsTeacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Northeastern US. PalenthologicalResearch Institution (affiliated with Cornell University).http://geology.teacherfriendlyguide.org/index.php/northeast“Twin Lakes.” Wikipedia.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twin_Lakes_(Connecticut)“What is Iron Ore?” Learning Geology.http://geologylearn.blogspot.com/2015/03/iron-ore.html>