Religion in Early Salisbury

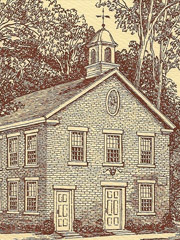

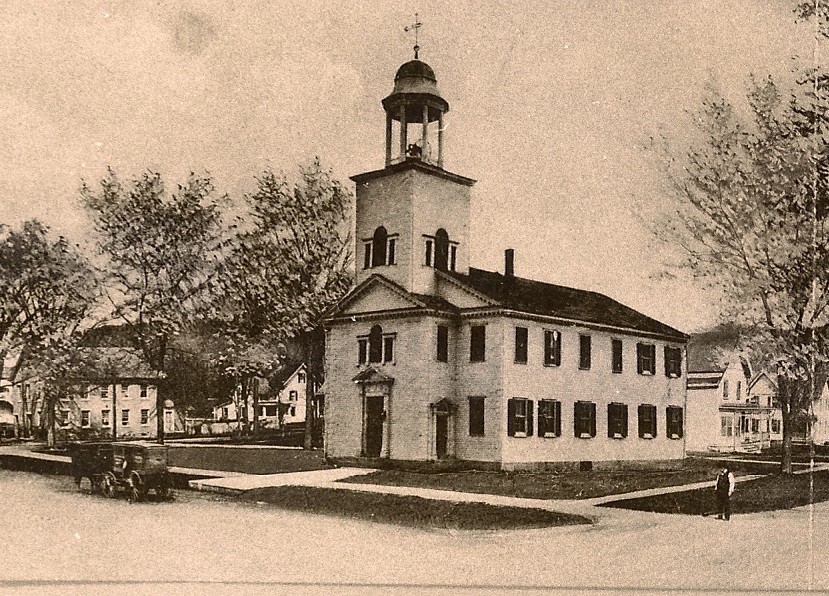

A town wasn’t considered settled until a church was established. Jonathan Lee, a licensed preacher of the Established Church (today’s Congregational Church of Salisbury, a member of the United Church of Christ), was ordained and became Salisbury’s first permanent minister in 1744, serving the town for 45 years. Religious services were held in Reverend Lee’s log home and later in a Meeting House that became the center of political, social, and religious gatherings. The Congregational Church today makes its home in the Meeting House built in 1800.

Other religious groups also came to the area. The first Methodist preacher arrived in 1787. The Rehobeth Methodist Church was built in Lakeville in 1816, and then chapels at Chapinville (now Taconic) in 1832 and Lime Rock in 1845. In 1822, Episcopalians built St. John’s Church in Salisbury and Trinity Church at Lime Rock in 1873.

Roman Catholics established their first mission at Falls Village, erecting a church in 1854. At the time, the parish included several other towns in Litchfield County and, for a period of time, was the only one between Bridgeport (CT) and Pittsfield (MA). In 1875-6, St. Mary’s Church (today, St. Martin of Tours, Church of St. Mary) was erected at Lakeville and formed into a separate parish. By 1883, a convent and parochial school had been built.